A rigid body system is an assembly of different parts which are joints, rigid bodies and forces. A joint connects two different bodies and gather all kinematic relations between those two bodies, allowing the creation of a relative displacement between the two bodies. This displacement is described by breaking it down into three parts, rotations, translations or the compositions of a rotation and a translation.

Rotation matrices form the so-called Special Orthogonal group \( SO(n) \). There are two groups within the latter which interest us as for now: \( SO(2) \) and \( SO(3) \). \( SO(3) \) is the group of all rotations in the 3-dimensionnal space. Its elements are matrices of size 3 by 3. \( SO(3) \) is useful for planar problems. It is the group of rotations in the 2-dimensionnal space. Its elements are matrices of size 2 by 2.

The set that brings together all the homogeneous transformations matrices is the Special Euclidean group \( SE(n) \). As with rotation matrices, there are two different groups, \( SE(3) \) for 3-dimensional transformations and \( SE(2) \) for 2-dimensional transformation, i.e. transformation in a plane.

To use quaternions for a \( SO(3) \) object we have several methods, we can do as in the \( SE(3) \) example in the e-lie chapter by removing the translation vector.

Or we can just consider one rotation instead of two. For example, in a landmark link to the robot itself, we consider the starting position as the origin of this landmark.

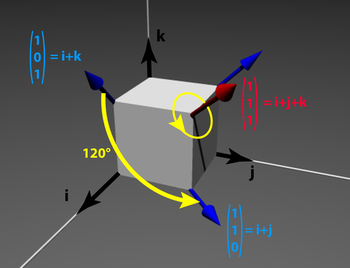

So let's consider a cube in the 3-dimensional space.

We want to determine the image of a vector \( \overrightarrow{v} \) by a \( 120° \) rotation ( \( \frac{2\pi}{3}) \) around the big diagonal of the cube, let's call it \( \overrightarrow{r} \). We have to use a passage through quaternion. We have \( \overrightarrow{v} = \overrightarrow{i} + \overrightarrow{k} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \) and \( \overrightarrow{r} = \overrightarrow{i} + \overrightarrow{j} + \overrightarrow{k} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \)

We compute the corresponding quaternion:

\( q = cos(\alpha/2) + sin(\alpha/2) * \frac{\overrightarrow{r}}{||\overrightarrow{r}||} \)

Therefore we have:

\( q = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2} * (\overrightarrow{i} + \overrightarrow{j} + \overrightarrow{k}) \)

And so we can compute the image of vector \( \overrightarrow{v} \) using:

\( \overrightarrow{v'} = q * \overrightarrow{v} *q^{-1} \)

we have:

\( \overrightarrow{v'} = \overrightarrow{i} + \overrightarrow{j} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \)

Determining the matrix corresponding to a rotation is not immediate, so that very often the physical problem is defined by the couple \( (\alpha,\overrightarrow{r} ) \). Another problem related to the composition of rotations is known as "blocking of Cardan" : we can see it in specific cases, for example when two successive joints have close or even aligned axes of rotation. In this case, a very large variation of the first angle does not change the position of the end of the device. A robot could then generate very strong violent movements without realizing it, due to the approximation of the calculations. To remedy these two points, we use quaternions.

Of course the cartesian product is essential for analysis and description of the movement in our Euclidean space. But here, it's specific to the lie algebra, this is different from the cartesian product which define our space. The cartesian product can also be used to create a specific space by associating spaces related to the lie algebra as \( SE(n) \) and \( SO(n) \) groups.

For example let's consider a wheeled robot like Tiago. It can only move on the ground. It is possible to assimilate the ground as a plane. The robot can rotate around the z-axis so we have to deal with a \( SE(2) \) object. Then we attach to this \( SE(2) \) object an articulated arm with four revolute joints spread out his arm, each has one degree of freedom of rotation so they are \( SO(2) \) objects. To deal with this set we use the cartesian product related to the lie algebra and we get a new space in which we are able to represent all the possible trajectories of the robot and its arm.

If you want to create a tangent space to simplify calculations of a trajectory it is necessary to use vector spaces. Indeed, a tangent space is a vector space that is the whole of all velocity vectors. Let's consider an object having a trajectory, all points of it have a velocity which is tangent to the trajectory and the space associate to one velocity and passing by one point of the trajectory is the tangent space.

Furthermore, by using vector spaces we have the possibility to use its properties as those of the Euclidean cross operator and linear combinations. However it is important to know that "vector space" is here related to Lie algebra and this is different for a vector space we used to deal with.